History of the Transcontinental Railroad

What was the Transcontinental Railroad?

The Transcontinental Railroad was the first continuous railroad line connecting the United States coast-to-coast. Authorized by Congress in 1862, it was to run from the Missouri River all the way to the Pacific Ocean. In practical terms, it tied the East (Atlantic) and West (Pacific) together by rail. This ambitious project fit the era’s spirit of Manifest Destiny – Americans believed technology and settlement would push progress westward. As John Gast’s famous painting suggests, the railroad was seen as bringing “progress” (and telegraph lines) out West. Once complete, it would let travelers go from Iowa to California in a matter of weeks instead of months.

Why was it built?

People wanted faster coast-to-coast travel and trade. In the 1800s, journeying across America over land was slow, dangerous, or required a long sea voyage around South America. A railroad promised to unite the nation economically and politically (especially important during the Civil War era). Congress sweetened the deal by offering huge incentives: each company got massive land grants and cash bonds for every mile of track laid (up to $48,000 per mile in tough terrain!). In short, linking East and West by rail would speed up mail, troop, and trade movements, help settlers reach new lands, and fully bind the country together.

Who built the Transcontinental Railroad?

Construction was split between two companies racing to meet in the middle. The Central Pacific Railroad (CP) built eastward from Sacramento, California, while the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) built westward from near Omaha, Nebraska. Both companies were incorporated just after President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862.

Labor was a huge effort. The UP crews (led by Civil War Gen. Grenville Dodge) hired thousands of Civil War veterans and Irish immigrants. Meanwhile, CP struggled to find enough workers in California and ultimately recruited about 50,000 Chinese laborers, who proved hardworking and vital for blasting through the Sierras. These men (often simply called “railroad workers” in history books) dug tunnels, built trestles, and laid tracks across deserts, plains, and mountains.

What challenges did the builders face?

Building across the continent in the 1860s was incredibly hard. Workers battled steep mountains, deep canyons, and brutal weather. For example, Union Pacific engineers had to erect the 130-foot-tall Dale Creek Bridge (shown above) to span a Wyoming chasm. Central Pacific crews blasted through granite in the Sierra Nevada using nitroglycerin and gunpowder, and even built hundreds of timber “snow sheds” to keep the track clear in winter.

On the prairie and plains, Union Pacific workers faced harsh weather and occasional attacks from Native American tribes fighting to defend their homelands. (Worker camps could also become rowdy frontier towns with saloons and gambling, as depicted in many Western tales.) Despite these obstacles, both railroads pushed ahead. The competition was fierce, since each company got paid per mile of track laid and wanted to be first to Utah. This rush led to some unsafe shortcuts, but ultimately they raced each other until only a few miles of track remained between them by 1869.

When was it completed?

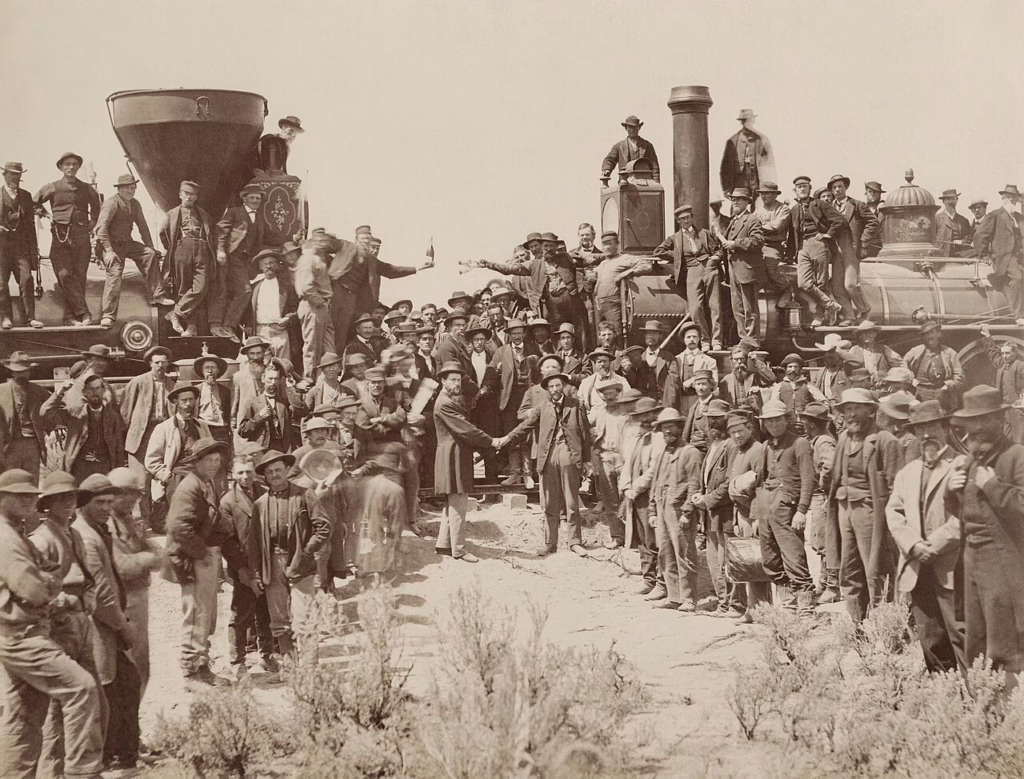

The final joining of rails happened on May 10, 1869. That morning, the last unfinished four miles of track were laid north of the Great Salt Lake, at Promontory Summit, Utah. In a festive ceremony, Central Pacific President Leland Stanford hammered a special 17.6-karat gold spike (the “Last Spike”) into a polished laurel tie. This act symbolically completed the “Colossal Railroad” that Lincoln’s Act envisioned.

Photographers captured the celebration (the famous “Champagne Photo” shows the two locomotive engineers spraying champagne on each other’s engines). In fact, one telling account notes: “The champagne flowed and engineers George Booth and Sam Bradford each broke a bottle upon the other’s locomotive,” as railroad bosses Dodge and Montague shook hands over the track. News of the completion spread fast – train travel from Iowa to California was now possible in about a week!

What impact did it have?

The Transcontinental Railroad revolutionized America. It slashed travel time across the country, accelerated commerce, and made the West feel much closer to the East. Instead of month-long wagon trains or long sea voyages, passengers and freight could travel coast-to-coast in about seven days. Western towns boomed: a stop in Omaha might turn into a city, and California goods reached Eastern markets quickly.

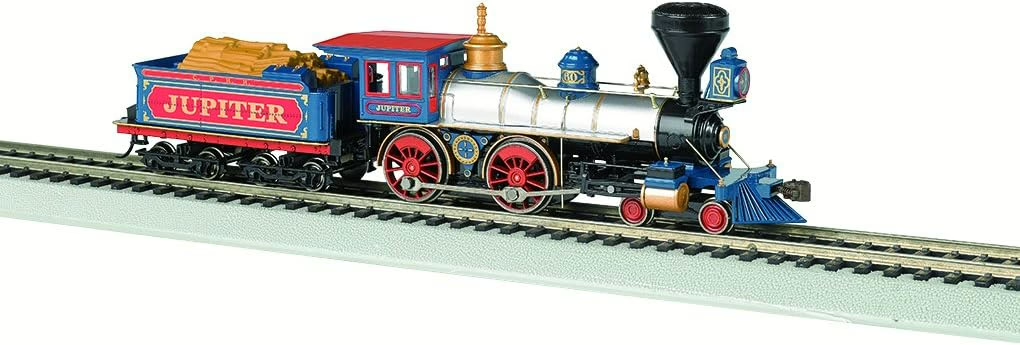

However, this rapid access also intensified conflicts. Thousands of new settlers poured into the West, which led to further clashes with Native Americans. The railroad itself foreshadowed the U.S. industrial age: iron rails, standardized time zones, and telegraphs along the line became symbols of the Industrial Revolution. For model-train hobbyists, this era sparked endless fascination – you can still visit the Golden Spike National Historic Site today to see replicas of Jupiter and UP 119, the two engines from that ceremony.

Key dates in the Transcontinental Railroad timeline

To recap, here are some major milestones in the railroad’s history:

- 1832: Early calls emerge for a rail link across America.

- 1845: Merchant Asa Whitney lobbies Congress to build a Pacific Railroad.

- 1853: U.S. Congress funds surveys of possible cross-country routes.

- 1861: The Central Pacific Railroad is incorporated in California.

- July 1862: President Lincoln signs the Pacific Railroad Act, authorizing CP and UP.

- 1863: Union Pacific is incorporated in New York and begins laying track east-to-west.

- 1866: Construction booms as Union Pacific (under Gen. Dodge) and Central Pacific (under C. Crocker) race west.

- 1869: May 10, 1869 – The Golden Spike ceremony at Promontory Summit completes the railroad.